The Forgotten Desirable Difficulty - Reduced Feedback

Robert and Elizabeth Bjork originally spoke of five desirable difficulties. Three of them get widespread PR: interleaving, spaced practice, and retrieval practice. The remaining two – contextual interference (a kind of interleaving but of contexts and not tasks) and reduced feedback get less with the last almost forgotten. This piece is about why reduced practice should be elevated to the level of the others.

We’ve all seen it. A student is ‘flying’ through practice. Every answer gets an instant tick or cross, every misstep corrected on the spot. The lesson feels smooth. Efficient. Productive. And then, a week later, the same student can’t do it. The ‘learning’ that we saw has seemingly evaporated into thin air.

That, in a nutshell, is why reduced feedback deserves a place among what Robert and Elizabeth Bjork call ‘desirable difficulties’: conditions that make performance during practice look worse and feel harder but make learning more durable and transferable (see this article in The American Educator or this article from Nicholas Soderstrom and Robert Bjork for a discussion of the difference between performance and learning). The uncomfortable truth is that the conditions that produce rapid performance gains are often the very conditions that undermine long-term learning. Immediate feedback is one of the best examples.

Reduced feedback is exactly what it sounds like: you limit the frequency or immediacy of feedback during training. Not because you enjoy watching learners struggle, and not because feedback is unimportant, but because you want learners to do something we too often outsource to teachers, apps, and rubrics: monitor their own performance, identify errors, and correct course. When feedback arrives after every attempt, learners can succeed while thinking surprisingly little. When feedback is less frequent or delayed, they must judge and retrieve. And that is where learning actually happens.

The Bjorks’ argument begins with a simple observation: immediate and constant feedback improves performance during practice, but can sabotage learning by creating a what can be called a fluency trap. Practice becomes smooth, and smoothness is mistaken for mastery. The lesson ‘works’ because the student keeps getting steered back onto the right track before they have a chance to build their own internal map. Frequent feedback acts like a Waze or Google Maps: you arrive at the destination, but you couldn’t do the route again without the voice telling you what to do next. In classrooms, that voice is the teacher, the answer key, the autocorrecting app, the constant confirmation or correction that makes the work look right in the moment. The price is dependency. The student learns, implicitly, that the job is not to understand or to evaluate, but to respond and wait for correction.

When you reduce feedback, something interesting happens. The learner is forced to rely on internal monitoring processes. They have to ask themselves whether their answer is correct or even plausible, whether a step follows logically from the preceding step, whether what they wrote matches the rule or the concept that they have been taught. This isn’t extra effort for fun or for the sake of it. It’s retrieval and self-evaluation. It’s the learner bringing relevant knowledge back online and using it to diagnose their own performance. And because that diagnosis is effortful, it strengthens memory and makes knowledge more stable and adaptable. You can think of reduced feedback as a way to train the learner’s internal teacher. If you always do the checking for them, that internal teacher never develops.

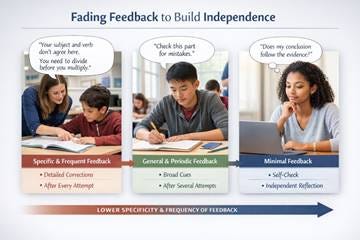

But there’s a second, often forgotten dimension of ‘reducing feedback’ that matters just as much as reducing how often you give it, namely reducing how much you give and how specific it is. In the beginning, especially for novices, learners often need feedback that’s concrete and corrective. Not a vague ‘try again,’ but rather: ‘your subject and verb don’t agree here,’ or ‘you divided before you multiplied,’ or ‘you’re using the wrong unit.’ That kind of specific feedback helps them build an initial, workable model of the task and prevents them from practising the wrong thing. Yet if we keep that level of specificity, we create a different kind of dependency. Students start waiting not just for the verdict, but for the diagnosis and the next step. They learn to outsource the thinking about what went wrong to the person with the red pen.

A powerful way to avoid that trap is to fade feedback in two directions at once. Over time you give feedback less frequently, but you also make it less detailed and more general. Early on, you might point to the exact place where the reasoning breaks and name the rule that was violated. Later, you might simply indicate that there is an error in a particular line and ask the student to find it. Later still, you might offer only a general cue: ‘Check your units,’ ‘Look again at the relationship between these two ideas,’ ‘Does your conclusion follow from your evidence?’ Notice what this does. The feedback gradually stops being an instruction manual and becomes a prompt for self-regulation; it becomes more epistemic and less corrective/directive. You’re not withholding help; you’re transferring responsibility. You’re, quite literally, training students to do what experts do, namely detect problems, locate them, classify them, and repair them.

This is also why so many lessons feel successful and then disappoint later. High performance during a session is often an illusion of competence. Correct answers produced with constant, highly specific support look like learning, but they may be little more than guided performance. True learning shows itself later, when the learner must retain and transfer without the scaffolds. Reduced and faded feedback tends to make practice look shakier and less fluent, precisely because the learner is doing more cognitive work. That is not a bug; it is the feature. The goal is not elegant performance at 10:15 on Tuesday, but durable competence at 10:15 next month.

Of course, reduced feedback can be implemented wisely or foolishly. Wisely, means you stop correcting every move and start designing space for the learner to notice patterns. One simple approach is to wait and give feedback after a short run of attempts rather than after each one. Instead of interrupting the flow problem by problem, you let learners complete a handful, then you discuss what went right and what went wrong. The feedback becomes less like a reflex and more like a diagnosis. Delaying feedback can be powerful for the same reason. A time gap between attempt and correction forces learners to ‘reload’ what they did. Immediate feedback is easy to process shallowly (sound of a buzzer: wrong, next) but delayed feedback asks the learner to reconstruct their reasoning: ask themselves what did I answer, why did I choose that, where did I go off track? That reconstruction is another form of retrieval practice, except the object being retrieved is the learner’s own thinking. You might even call it second order retrieval, but that’s another blog.

In skill-based domains, there’s a further refinement that teachers often do intuitively. Good teachers don’t comment on everything. They intervene when errors fall outside of an acceptable range and let students self-correct the small stuff. That’s not neglect; it’s training autonomy. If you correct every minor slip, you make the learner a passenger in their own learning process instead of the driver.

WARNING: The concept of desirable difficulty has been used as a justification for all sorts of pedagogical nonsense. Reduced feedback is desirable only when learners have enough foundational knowledge to eventually succeed. If you withhold feedback, or make it too general too soon, for a true novice who can’t diagnose errors, you don’t create productive struggle; you create confusion and frustration. The learner doesn’t think, ‘Let me evaluate my approach.’ They think, ‘I have no idea what’s going on.’ So the question is never ‘Should we reduce feedback?’. The question is: ‘When can this learner plausibly self-correct, and what supports help them reach that point?’ That is why fading feedback, both in frequency and in specificity, is often safest way to go. You start supportive and become demanding as the learner becomes capable.

The best practical test is to watch what happens as you fade. If learners respond by checking, explaining, comparing their work to a standard, and correcting themselves, you’re building the right kind of difficulty. If they respond by guessing, giving up, or repeating the same error blindly, you’ve removed guidance before they had the knowledge to use it. In other words, you haven’t created independence; you’ve created abandonment. The art is to reduce feedback in ways that force learners to do the thinking you ultimately want them to own, while still ensuring that errors don’t fossilise into misconceptions.

So yes, reduced feedback may make your lesson look and feel less smooth. It may even make you feel less helpful. But if your goal as a teacher is to develop learners who can perform without you, learners who can monitor, adapt, and transfer, then smoothness isn’t the metric. The real metric is what students can do later, in a different context, without Waze o Google Maps. Reduced feedback, and especially feedback that’s deliberately faded from specific to general, is a quiet but powerful way to shift responsibility from the teacher’s correction to the learner’s cognition. And that’s exactly what education is supposed to do.

Important!!

Since someone hacked my Twitter/X account and Twitter/X won’t do squat to help me recover it, this Public Service Announcement:

Please use your Twitter/X account to alert people to the fact that they should leave my old account (@P_A_Kirschner) and report it as someone impersonating me.

You can now follow me at my new account (@New_Old_Paul).

Some readers may be surprised to know that this concept has been extensively studied in a literature from the behaviorists! In 1957, C. B. Ferster and B. F. Skinner published a detailed summary of experimental research that included this topic. It’s not a philosophical treatment; it is a nuts-and-bolts scientific analysis. The book was (and still is) called “Schedules of Reinforcement” https://lccn.loc.gov/57006418.

The bit about learning evaporating into thin air really resonated. How do you think AI systems could integrate reduced feedback effectivelly? Such an insightful article!