Make the Connection

I’ve written a number of times about research showing that taking notes by hand or learning to recognise and recall letters is better when done by hand as opposed to using a keyboard. While the research results are clear that it’s better to physically write than to keyboard, I’ve always explained why based on insights from cognitive psychology. This study by F. R. (Ruud) Van der Weel and Audrey L. H. Van der Meer from the Developmental Neuroscience Laboratory at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway adds a new dimension to explaining why.

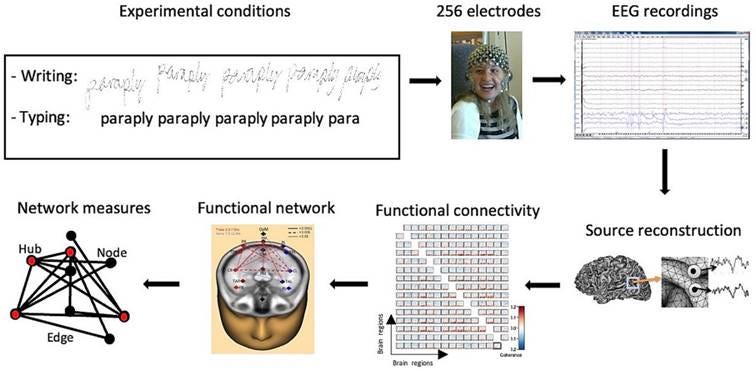

In the study, 36 university students were equipped with a high-density EEG cap with 256 electrodes to measure very fine-grained patterns of brain activity. Students sat in front of a large touch screen where a series of common words appeared. For each word, they had to do two things in separate trials, namely write the word cursively by hand with a digital pen or type it with their index finger on a keyboard.

The research focused on the first few seconds of each trial, when the student was actually writing or typing, and looked not only at how active the brain was (duh), but also at how different brain areas worked together. In other words, they were interested in functional connectivity, on which regions were synchronised with each other during handwriting, and which regions during typing. They wanted to know/learn what kinds of brain networks are formed when we handwrite compared with when we type.

When students wrote by hand, the data showed widespread, coherent connectivity across the brain, particularly between parietal and central regions which are involved in integrating vision, movement, body awareness, and aspects of attention and language. When the researchers plotted the connectivity patterns, handwriting trials showed what the researchers called dense “webs” of interaction: hubs and nodes connecting left, right, and midline parietal areas with central motor regions. In the typing condition, these networks were much weaker or even absent. The brain was active as the students were seeing words and moving their fingers, but not in the same kind of integrated, learning-related connective way. Put simply, during handwriting, the brain looks like it’s gearing up to learn and remember. During typing, this “learning-ready” pattern is far less pronounced.

When you write a word by hand, a lot has to happen at once. Your brain must control fine, precise finger movements to shape each letter. It must constantly monitor the visual form of what is being written: is that loop at the bottom of the “b” closed, is that stroke straight or slanted, does the letter sit properly on the line with the tails (e.g., the tail of the “g” or the “q”) nicely below it? You brain has to integrate what’s known as proprioceptive information; the internal sense of where your hand and fingers are in space. And finally, it must link all of this to language systems that represent the sounds and meanings of the word. This all results in a very rich and intricate sensorimotor experience: a flowing pattern of movement, vision, and body-sense that unfolds over time combined wit cognition and meaning. Neuropsychologically speaking, this kind of multimodal engagement is exactly the sort of thing that builds strong, distributed memory traces. It gives your brain a number of different routes to encode and later retrieve the word – not just what it looks or sounds like, but also what it feels like to produce it.

In the typing condition, the story is different. When you press a key, the movement is relatively simple and doesn’t change much from letter to letter. Pressing an “a” feels no different from pressing a “b” or “c”. The letter forms appear on the screen pre-packaged; the movement didn’t construct them stroke by stroke. Neuropsychologically speaking, that means fewer distinct sensorimotor cues for the brain to bind together with the visual and verbal aspects of the word. The EEG results reflected that: the kind of integrated, learning-related connectivity seen when handwriting simply didn’t appear to the same extent when keyboarding. The brain is doing something, but it’s not linking movement (i.e., motor control) and cognition with each other as handwriting did.

This experiment fits into a broader pattern of findings about handwriting and learning. Other work has shown, for example, that children who learn letters by writing them recognise and remember those letters better than children who only look at them or type them. Studies in taking notes show that doing this by hand leads to better remembering than when done via a keyboard. Also, studies in early literacy have found that handwriting training supports spelling and letter knowledge more strongly than typing practice.

What does this all mean?

First, handwriting is a form of neurocognitive training. You’re not only practising a motor skill. You’re shaping the brain networks that integrate vision, movement, and language which is closely tied to learning and memory. That’s especially important in the early years, when those circuits are still developing.

Second, for tasks meant to achieve deep understanding or long-term retention, taking notes by hand, sketching diagrams, writing summaries and so forth trumps keyboarding. In those moments, learners aren’t just recording information but are building integrated networks that support recall and transfer.

Finally, though keyboards and tablets have their positive points (e.g., accessibility/sharing, collaboration, speed, legibility) overuse, especially in early and middle years, may undermine a powerful way of engaging students’ learning systems.

Five reasons to keep handwriting in a digital classroom:

Handwriting is good for the brain: When students write by hand, their brains show richer connectivity between visual, motor, and language areas in frequency bands linked to learning and memory. Handwriting engages the “learning brain” more deeply.

Early handwriting builds later literacy: Practising letters and words by hand helps wire up the neural systems that support fluent reading and writing. As Donald Hebb wrote: “neurons that fire together, wire together”.

A screwdriver isn’t a chisel: Use handwriting when the goal is understanding and remembering (note-taking, summarising, working through ideas). Use keyboards when the goal is producing and sharing (final drafts, long essays, collaborative documents). They are not interchangeable.

Thinking on paper sticks: Quick handwritten activities—one-minute recalls, margin notes, concept sketches—combine retrieval practice with rich sensorimotor activity; ideal for long-term retention and transfer.

Handwriting is still relevant: It’s not nostalgia! Thing weren’t always better in my day! The most modern neuropsychological research shows it supports the brain systems that make learning last.

For educators, the practical conclusion is: when you really want something to “stick”, there are good neuropsychological arguments for putting a pen – or a stylus – in students’ hands. For other reasons like speed, neatness, and ease of sharing, the keyboard has an advantage. It’s not about choosing one or the other, but using both wisely, in ways that respect how we learn.

Van Der Weel, F. R., and Van Der Meer, A. L. H. (2024). Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity: a high-density EEG study with implications for the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology. 14:1219945.

Wondering what the significance of this would be for young learners with an SLD like dysgraphia? Is there any research happening in this space?

Excellent guidelines! You say: “Handwriting is good for the brain: When students write by hand, their brains show richer connectivity between visual, motor, and language areas in frequency bands linked to learning and memory.” For beginning readers, cognitive psychologist Diane McGuinness promoted saying each phoneme as the grapheme is written to aid retention of sound-spelling correspondences. No research has been done on this practice, but it seems to follow from what you describe. Is this an appropriate extrapolation?