Learning by getting it wrong (on purpose)

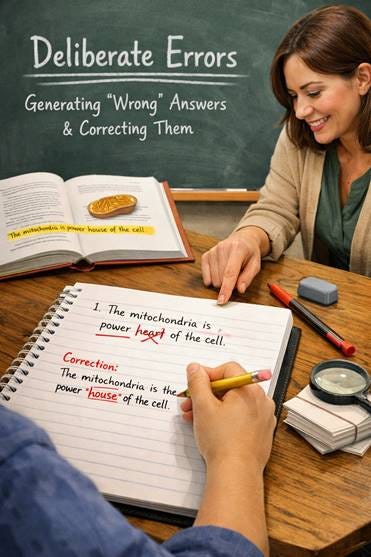

Deliberate errors

Disclaimer:

This isn’t about learning through failure or productive failure or productive struggle

or any of those failing approaches that let kids flail.

It’s more a possible extension of retrieval practice with hints of interleaving.

For years, cognitive science has told us something that still feels counterintuitive in classrooms: trying to remember (retrieval practice) beats rereading, even when it feels harder. Retrieval practice has earned its reputation as one of the most reliable learning strategies we have. But a new paper by Qiang, Ma, and Li asks a sharper question: Might deliberately making the wrong answer while knowing the right one work just as well as retrieval practice, or even better, especially over time?

Their study Learning from errors: Deliberate errors enhance learning published in Contemporary Educational Psychology, doesn’t romanticise error or failure. Instead, it tests a very specific and carefully controlled strategy, namely what they call deliberate errors. This is where learners intentionally generate plausible, conceptually related but incorrect answers and then immediately correct them. The key idea is not “learn from your mistakes” in the everyday sense, but “engineer mistakes as part of encoding.” And crucially, the authors do what good learning science should do: they compare this new strategy not to a straw man, but to retrieval practice itself.

Experimental design

Across three experiments, undergraduate students learned core psychology concepts; term–definition pairs taken from a standard introductory textbook. These aren’t trick questions or higher-order applications, but the kind of foundational knowledge students are expected to master early in a discipline.

First, participants were randomly assigned to one of three learning conditions, and the total study time was carefully matched. In the restudy condition, students read the definition, copied it verbatim, and underlined what they thought were the key parts of the definition, mirroring what many students naturally do when revising.

In the retrieval practice condition, students studied the material and then had to recall the definition from memory with the material hidden. In Experiments 1 and 2 this was a simple study–test sequence without feedback. To combat the criticism that this isn’t the way retrieval practice is or should be used (i.e., a one-shot practice opportunity), in Experiment 3, retrieval practice was strengthened. Here, students went through a study–test–study–test cycle, with opportunities to re-expose themselves to the correct information.

The deliberate error condition is the most interesting. Here, students first studied the correct definition. Then, with the material still visible (so this is not guessing), they intentionally altered key parts of the definition to create a reasonable but wrong version. For example, “Memory is the psychological process…” might become “Memory is the physiological process…”. Immediately after, they corrected the error by writing the correct term next to it: Memory is the physiological (psychological) process…”. Importantly, students were trained and monitored to ensure the errors that they thought up were conceptually related, and not random or silly. Generating irrelevant errors disqualified the attempt. This matters because it keeps the task cognitively focused. Learners aren’t flailing; they’re actively contrasting what a concept is with what it isn’t.

Learning

In the first experiment, students were tested immediately after learning. The result is reassuringly boring in the best possible way. Deliberate errors and retrieval practice both led to almost identical performance and both were clearly better than restudy. This alone is important. It shows that deliberate errors aren’t some flashy shortcut that produces instant gains. They don’t outperform retrieval practice when memory is still fresh. If the story ended here, deliberate errors would be “interesting but unnecessary.” Fortunately, the story doesn’t end here.

In Experiment 2, a delayed test one week later was taken with no additional study in between. Now the pattern changed. Deliberate errors produced significantly better retention than retrieval practice, and both were better than restudy. As I stated earlier, sceptics might reasonably argue that retrieval practice was underpowered here. After all, a single retrieval attempt without feedback is not how retrieval practice is usually recommended or implemented. The authors anticipated this criticism and addressed it directly in Experiment 3.

Here, retrieval practice was given a fairer fight. Students in that condition went through two rounds of retrieval with restudy in between. The restudy group also received additional exposure to match time on task. Both immediate and delayed tests were administered and the results replicated the earlier pattern. On the immediate test, deliberate errors and retrieval practice again performed similarly while on the delayed test, deliberate errors again came out on top.[1]

Why might deliberate errors work?

The authors offer several complementary and not competing explanations, all of them grounded in existing theory rather than post-hoc storytelling (postdiction). The first comes from search and diagnosticity. Both retrieval practice and deliberate errors help learners narrow the search space for correct answers. But deliberate errors do this by explicitly activating competing, plausible alternatives and then eliminating them. In other words, learners don’t just strengthen the correct path; they weaken the incorrect ones.

A second explanation focuses on knowledge discrimination. By thinking about what a concept isn’t, learners sharpen the boundaries of what it is. This is closely related to findings from research on refutation texts, contrastive learning, and interleaving. Memory benefits not just from repetition, but from differentiation.

Finally, the authors offer a contextual explanation. Making and correcting errors creates distinctive episodes which may form richer, more retrievable memory traces than simply recalling the correct answer, especially over longer delays.

What’s striking is that none of these explanations rely on struggle for its own sake, or on failure-as-character-building. The errors are deliberate, constrained, and immediately resolved. This isn’t productive failure, discovery learning, or “let them struggle and figure it out” (Luctor et Emergo). Learners already know the correct answer before they err.

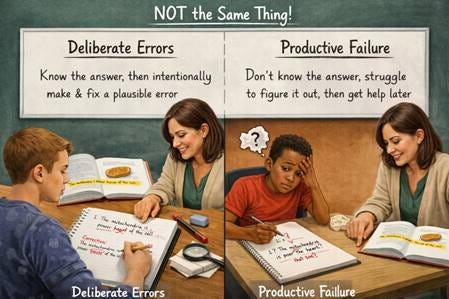

Why this is not productive failure

It’s tempting to see deliberate errors as another variant of productive failure. That, however, would be a mistake. The two approaches differ on a fundamental dimension: what learners know at the moment they err.

In productive failure, learners are asked to solve problems before they’ve been taught the canonical solution. Failure is expected to prepare them for later instruction by activating prior knowledge and revealing gaps. Whether this works depends on learners’ ability to extract structure from their unsuccessful attempts—a capacity novices often lack. I discussed why this type of failure doesn’t work in a recent piece here or here.

In deliberate error learning, the sequence is reversed. Learners already know the correct answer before they are asked to make an error. The error isn’t a signal of ignorance but a designed contrast of the error against known correct information. Learners aren’t searching blindly; they’re deliberately violating a known constraint and then repairing it. Cognitively, this is much closer to contrastive learning and discrimination than to discovery.

This difference matters. While productive failure relies on learners learning from not knowing, deliberate errors rely on learners learning by differentiating what they know from what it isn’t. The former assumes that schema construction can begin through failure while the latter assumes that schemas are already present and can be sharpened through contrast.

The ever-present metacognitive problem

One of the most sobering findings is that learners consistently underestimated, as they also do in retrieval practice, the effectiveness of deliberate errors. Even when the strategy led to better long-term retention, they didn’t judge it as particularly effective. Retrieval practice, which is often rated as less effective than rereading, was rated more favourably than deliberate error, and restudy often felt just as good. This fits neatly with a broader literature on metacognitive illusions (maybe something for a follow-up book to Instructional Illusions?). Strategies that feel fluent feel effective, even when they’re not. Deliberate errors feel odd, uncomfortable, and counterintuitive. Learners don’t naturally adopt them without guidance.

Design requirements

As promising as deliberate errors are, the findings don’t imply that they work everywhere or for everyone. First, prior knowledge is essential. Learners must already have access to the correct information. Without this, deliberate errors collapse into guessing, and the benefits disappear.

Second, the errors must be plausible and conceptually related. Random or superficial errors don’t promote discrimination; they simply add noise. The studies carefully constrained error generation, and that constraint is part of the intervention, not an incidental detail.

Third, immediate correction is non-negotiable. The learning benefit comes from the juxtaposition of wrong and right, not from leaving learners in error. Delayed or missing correction would likely undermine the effect.

Finally, the task domain matters. The study focused on well-defined conceptual knowledge (term–definition learning). Whether similar effects hold for complex procedural skills or ill-structured problem solving remains an open empirical question.

These four requirements aren’t weaknesses. Deliberate errors work not because error is good in itself, but because the errors are carefully engineered to serve learning goals.

Teaching takeaway

This study doesn’t suggest that teachers should encourage students to fail, guess wildly, or replace instruction with error-making. The deliberate errors used here are tightly defined, low-risk (actually no-risk), and embedded in correct information. They’re closer to contrastive encoding than to failure. What it does suggest is that errors can be designed. When errors are plausible, immediately corrected, and cognitively targeted, they can enhance learning in ways that even strong strategies like retrieval practice sometimes don’t.

For teachers, the challenge isn’t to celebrate mistakes in the abstract, but to design tasks where mistakes are informative, safe, and epistemically meaningful. Deliberate errors, used carefully, may be one way to do that.

ABSTRACT

Deliberate erring is an effective learning strategy, comparable to retrieval practice, However, learners often experience metacognitive illusions regarding both strategies, making their adoption challenging, particularly for deliberate errors. This study compares the effectiveness of deliberate errors (S–D) with retrieval practice (S–T) and restudy (S–S) across three experiments: Experiment 1 focused on immediate testing, while Experiment 2 examined delayed testing. In Experiment 3, the impact of deliberate errors (S–D), retrieval practice with feedback (S–T–S–T), and restudy (S–S–S–S) was assessed in both immediate and delayed tests. Results showed no significant difference between deliberate errors and retrieval practice in immediate tests, regardless of whether retrieval practice included feedback (Experiment 3) or not (Experiment 1). However, deliberate errors consistently outperformed restudy. In delayed tests, deliberate errors significantly outperformed retrieval practice, whether with or without feedback, and both strategies were superior to restudy. The results indicate that, compared to retrieval practice, deliberate errors show better memory retention over a longer time interval. The findings of this study provide empirical evidence for the application of deliberate error, retrieval practice, and restudy strategies.

Qiang, X., Ma, X., & Li, T. (2025). Learning from errors: Deliberate errors enhance learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 82, 102379.

[1] It must be noted that this isn’t the result of a straw man or weak comparison. Deliberate errors outperformed retrieval practice even when retrieval practice was strengthened and feedback was available.

I really appreciated the nuance of how to engineer constrastive errors to advance student learning. Thank you- great piece!

I wonder if this is part of why creating MCQs in PeerWise works. You have to create the right and wrong answers.