Language

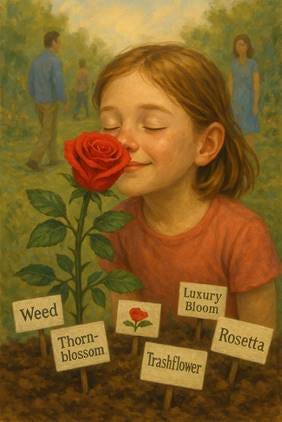

What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet

What's in a name? “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet” [1]

I recently wrote a column for a Dutch teacher’s journal in which I discussed a study about the effects of explicit instruction on children with specific learning problems. It was about whether explicit instruction had a positive effect on learning for children with dyslexia and ADHD, or better said who were diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD. After the editor went through the piece and — thankfully — improved the flow and corrected some phrasing, I got the revised version back. I agreed to all the changes, except for one: his suggestion to change ‘children with learning problems’ to ‘neurodivergent children’.

Let’s just say: I didn’t agree.

I wasn’t writing about neurodivergent children, but about children struggling to learn for whatever reason. I could probably write a full-length article about the conceptual issues relating to neurodiversity here, but will limit it to explaining my objection for changing the term in three short parts.

Note 1: PLEASE, hear me out and don’t jump to unfounded conclusions on what you think or want to believe that I’m saying. This is a blog about language (see the title) and not about whether specific children need or should get special help when they struggle for whatever reason. Of course they should! Even grumpy old men like me know that.

Note 2: Since this piece is about LANGUAGE, if you still disagree with what I write after carefully reading it, then be civil and thoughtful if you choose to respond. I don’t like blocking people, but do it quickly when people are disrespectful both in intent and language.

Language doesn’t fix stigma — it evolves with it

Some people consider speaking of children with learning problems to be insensitive, discriminatory, outdated, or stigmatising. Yes, sometimes language does discriminate and words can really hurt. But does replacing it with a new term really change or improve things?

History offers a long list of examples where once-accepted – even medical - terms became pejorative, not because of the words themselves, but because of the meaning and eventually the stigma that people/society attached to them. People were once medically classified as idiots (IQ<25), imbeciles (IQ 25_50), and morons (IQ 50_70). In time, these terms were used in disparaging and derogatory ways and stigmatised people. They were eventually replaced by what was considered to be kinder terms like mentally retarded, feeble-minded, or mentally deficient. These too were, in time, used in disparaging and derogatory ways which stigmatised people so they were replaced by mentally handicapped, and later disabled, differently abled, or challenged. And now they are neurodivergent.[2]

You see where this is going. We change the labels, but the problem isn’t the label — it’s how society treats people. It’s entirely possible (likely, even) that neurodiverse or -divergent, despite their current positive ring, will become tomorrow’s problematic term. Language drift is inevitable, and attaching too much moral or ideological weight to any one term is risky.

What exactly does ‘neurodivergent’ mean?

In my understanding, neurodiversity refers to natural variations in how people think, perceive, and process information — and the idea that these differences are part of normal human variation, not something broken that needs to be fixed and neurodivergent describes individuals who think, perceive, and process information differently from what is considered to be neurotypical. They are hopeful, humanistic concepts. But they’re also, in practice, extremely broad. So broad, in fact, that they become almost meaningless. If we all think, perceive, and process differently — and we do — then aren't we all neurodiverse and isn’t neurotypical a non-existent thing?

And here’s the thing: once we start applying the term neurodiverse to specific conditions like dyslexia or ADHD (or for that matter any of a list of other learning problems, and that list seems to grow larger daily), we also medicalise and pigeon-hole them. And often, once something is medicalised, a solution must follow — a therapy, a programme, a pill, a crutch [i].

While support, a therapy, a solution can be very good or even necessary, we should be careful about how much explanatory power we grant to the label itself and what it means to those who are labeled (see the next section).

Shifting the problem onto the child

Finally, calling a child neurodiverse or neurodivergent can subtly shift the responsibility for their struggles onto them — rather than examining other factors, including the learning environment. With neurodiversity it’s their brain, their wiring, their difference. Do you see the stigma rising here? But what if the problem lies not in the child, but in the system?

I, for example, have children who attended an alternative school (I was against it but lost the fight) that downplayed phonics, repetition, fluency, practice, and so forth. Play and fun were primary, drilling was “killing” and whole word instruction and not phonics was the norm. My kids were labeled for the rest of their lives and they believed it. Maybe, just maybe, they just had had poor reading and writing instruction. That doesn’t make their struggle less real or less problematic, but it shifts the question of why they struggled. Maybe it wasn’t them? Maybe they didn’t suffer (yes suffer) from dyslexia, but from bad education and poorly informed and trained teachers?

We now have large numbers of children, for example, diagnosed with dyslexia and dyscalculia. Are all these diagnoses the result of neurological variation? Or could some — maybe many or even most — be due to ineffective instruction? In the Netherlands, for instance, realistic mathematics education and whole-word reading approaches have arguably left many students without the fluency or foundations they need. More than 30% leave school at 16 as functionally illiterate (they can’t read an official letter or the instructions accompanying a box of aspirin) and 50% are unable to do the simplest mathematical calculations (what is the price of something that was €100 and is now 25% discounted?). And those children are then labelled, remediated, and sometimes pathologized and stigmatised.

Ironically, these same children labelled as neurodiverse often receive remedial lessons or specialised tutoring. But if neurodiversity is a strength or a unique cognitive profile, why do we intervene? If it’s “not something broken that needs to be fixed”, why are we spending so much time and money to fix it? Why not just accommodate it? The moment we start pulling children out for extra help, we’re acknowledging — whether we say it or not — that something isn’t working; that something is broken and needs to be fixed and not just a different way of thinking, perceiving, and processing information.

A final note on labels

Let me be clear: I’m all for respectful language and inclusive thinking and live by this daily. Politically speaking I’m fairly left of centre and some might even call me woke in that respect. But I worry when new terminology obscures old problems — or makes it harder to talk clearly about what children are actually experiencing. Sometimes a child is just struggling to learn. And maybe, before reaching for the newest sympathetic label, we should first ask: why? And then fix it! Don’t confuse word choice with actual change.

[1] William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act II, Scene II (1597 printing)

The quote means that the inherent qualities of something are not changed by its name or label and suggests that names are arbitrary and don't define the true nature or essence of a thing.

[2] We see this in many situations, for example with respect to height, stature, weight…

[i] In the Netherlands 8-10% of children receive the diagnosis of dyslexia (with many more white middle- and upper class kids getting the diagnosis than poorer children and/or children of colour) while experts estimate that it’s actually maximally 2-3% of the population. Approximately 30 million euros are spent yearly ‘treating’ it.

Also, this past week, it was reported that in the Netherlands the number of people diagnosed with ADHD has more than quadrupled in the past 20 years, an increase that has gone hand in hand with the broadening of the definition for this neurodiversity in the DSM-5 and the pharmaceutical lobby to get this enacted.

Brilliant in every way! Have you been following the work of Julian Elliot (The Dyslexia Debate Revisited). Here’s a 30-minute video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N7KR7gwDPXk&t=11s) expressing his views that we don’t need to come up with labels—we just need to address the problems students present. Thanks so much for so eloquently expressing this.

I want to give this a standing ovation! I want to see more people writing about this!